I’d been writing my memoir for three years when I called my first draft DONE and looked for an editor who could tell me what was missing. “I know exactly what’s missing,” editor Morgan Farley said, two weeks after I handed her a 400-page manuscript. “For starters, you have four books in one. I’ve noted the number of pages in each and would suggest you go with the one with the most pages, because that seems to be where your energy is.” Early in the process I’d shared the first 60 pages with my goddaughter, an author of books for middle-school-aged children.” “Shirley,” she said, “you need to finish this. Others will want to read it.” Really? If that’s the case I’d better go the distance and make it worthwhile, I thought. “But you need to write about Joe (my first husband),” she said. Taking her advice to heart, I wrote about Joe and once I’d done that I figured I might as well write about my philandering Greek lover and my troubled mother.

Lesson #1: A memoir is not a beginning-to-end autobiography. It’s a slice of your life, limited in scope, with a unifying theme. My scope? 2 ½ years. Theme? Finding love late, losing it too soon yet choosing to love again. Lesson #2: Sources. Some memoir writers journal, others keep diaries, letters and scrapbooks. In college I was a history major with a healthy regard for original sources. My original sources for Banged-Up Heart? Emails and a detailed journal. Good recall of conversations helped too. With the scope narrowed and the theme clear, there was still a lot missing and yet, I thought I had put down everything! Lesson #3: A memoir is more than the visible, external story. In my 2 ½-year story, there was a lot of action, a lot of drama, but action alone is not enough. Explicit in the definition of memoir is “intimate experience,” intimate meaning deep within. I had to go deep inside, reliving some painful moments, to find the unvarnished truth. And once I acknowledged it, I had to have the courage to put it on paper and let the chips fall where they may. This was hard for me, initially, because I’m not by nature introspective but with questions and guidance by my editor, I found I could be. Often, a simple question, e.g., What were you feeling? could, once I was home alone, trigger recall of intensely felt emotions. Lesson #4: Use the tools of novel-writing to make your memoir come alive. Create scenes, characters and dialogue. Resolve tension. Show rather than tell. As a longtime business writer, a scene was where a meeting took place. Dialogue? Reporting contrasting views by one or more speakers, while germane to business writing, was hardly a conversation. Scene-setting: We create scenes to help anchor the reader with where we are and what’s happening, with enough detail to give a sense of place but not too much – too much detail can inhibit the reader’s imagination. A scene takes place in one place and one time period. Whenever you move location or time in a significant way, it becomes a new scene. In a scene, you want the reader to see, hear and smell, even taste and touch everything you see, hear, smell, taste and touch. This gives the reader a sense of being there, in the moment. (See page 100 in Banged-Up Heart.) More on creating scenes: A scene is a moment when something happens and someone responds in the outer world. The reader wants to see you externally and internally. Tell your story as you would to your best friend, allowing a kind of intimacy to happen.

Lesson #5: Reflection. A memoir is more than using fiction techniques. In memoir-writing, part of the process is reflection. You have a point of view at a certain time, but you need to look back and reflect on that point of view from where you are now. (See examples in Banged-Up Heart on pages 21, 33 and 71.) Lesson #6: Unpack key moments. Slow down so the reader sees and hears what you see and hear, so the reader is in your skin. (Beginning on page 258, you’ll see nearly two pages that started out as nine lines before I unpacked the moment.) Slowing down was hard for me. When I was working with lobbyists in a fast-paced environment, I did a lot of things almost simultaneously. On slowing down by author Natalie Goldberg: “Writing can train you to wake up. I had to get slow and dumb (not take anything for granted) and watch and see how everything connects.” Lesson #7 Voice. When you slow it down, your natural voice can come out. Lesson #8: Tell on yourself. The more you can tell on yourself, the more the reader will like you and trust you as a story teller. (See page 50, my reaction to John’s revealing my age to Carla.) Lesson #9: Use slang or colloquial expressions. These communicate a little of who you are and make the writing more lively. (See “chowing down” on page 21; “hardly ready for prime time” on page 22.) Lesson #10: Show feelings through what the body does. (Examples from Banged-Up Heart and a few from Jennifer Lauck’s Blackbird: Instead of “John listened attentively to my story,” I wrote “His eyes never left my face.” Others: I nodded my understanding; her eyes opened wide; alarm rang in my brother’s voice; my stomach moves around and around the way it does when I’m hungry except I’m not hungry; she breathes in and out like she can’t get enough air and sweat dots poke out on her top lip. Lesson #11: Revise by free-writing. I had to re-live some painful moments by re-entering the experience in mind and body. To do this, I often set time limits, e.g., 15 minutes on a particular moment, using pen on paper, NOT computer. Lesson #12: Pacing. When I wrote my first draft, I wrote down everything without a thought about pacing or structure. But in rewriting, I had to think about pacing. When looking at a paragraph, think about it in terms of action. What are you trying to make happen? And weigh whether stuff is extraneous. Too much can slow the narrative. With our own lives, it’s hard not to think everything is important, but you have to include only those things that are good for the story. (The sentence on page 2 of Banged-Up Heart, “Would you like to take a walk?” replaced three pages of extraneous stuff in my first draft – a lot of detail about what I was wearing and how John and I walked down the porch steps to the public sidewalk -- I cut all but this one sentence.) Pacing as it relates to chapters: Look at each chapter and ask: Does it stand alone? Does it have a beginning, middle and end? You need an arc in each chapter where something happens. Episodic does not a story make. Each chapter has a purpose, structure and action that give it momentum. Each chapter should have one full scene with dialogue, characters and description. Lesson #13: When writing about travel, write about the unordinary. For example, many people have not been to Botswana (pages 75-80) but in writing about France where many readers have traveled, the challenge was to make it new by experiencing it through my eyes, e.g., What was it like to climb all those steps to the abbey at Mont Saint-Michel? (See pages 105-106.) Lesson #14: Logistics -- Don’t get hung up on logistics, getting from place to place – it’s TMI (too much info.) Lesson #15: Remember the power of short, declarative sentences. They add tension and a sense of urgency. (See 148, in emergency room.) Lesson #16: Revealing intimacies – Someone asked if I had any qualms about revealing intimacies found in my memoir. Yes, initially I did. But when my editor asked questions I had to answer, I became more comfortable with revealing and decided that if I wasn’t hurting someone else, I would tell the truth. Reviewers have called Banged-Up Heart “remarkably candid,” filled with “. . . and shocking honesty.” Lesson #17: The strength of a memoir is the weaving together of present time with reflection on times past. This is how we experience life. We’re in present time but going in and out. Present and past are possible when you slow the action and your story becomes rich with layers of memory and feeling. Although I discarded all in my first draft except the book about John, I was able to use a lot of the writing I’d already done. For example, Joe comes in as my backstory in the context of meeting John. (See pages 3-5.) I selected anecdotes from the Joe story and placed them in the narrative about John and me. By doing this, my story became more poignant. It gave the story of John and me more depth and me as a character more depth and vulnerability and makes it easier for the reader to identify with me.

1 Comment

By Shirley Melis “I came here expecting to buy produce, and here I am, buying books!” The tall man in khakis and a blue polo shirt cradled three books in one arm while his wife listened to another author at the table pitch her book. Home-Grown Authors, sponsored by the New Mexico Book Association, is the brainchild of Maxine Davenport, a local author who writes compelling short stories and novels about strong women. Love Is a Legal Affair is her latest. As many as six local authors can be found indoors at Santa Fe’s Farmers Market every Tuesday morning until Thanksgiving. Their works of fiction and non-fiction run the gamut from westerns and murder mysteries to memoir and travel stories. • Gone to the Dogs is author Tom Lohr’s story of his 103-day odyssey to find the best combination of baseball and hot dogs at major league baseball parks in North America. • Belinda Perry, author of An Old Woman’s Lies, also writes westerns, using the name William Luckey. “When I started writing westerns, I figured no one would buy a western written by a woman,” Belinda confides. • Taking the act of walking seriously is author Michael Metras’s mission. Germany to Rome in 64 Days: Our Pilgrimage is Michael’s book about a walk he took with his wife, whom he met on a walk across northern Spain. On the Germany-to-Rome trek, each went through nine pairs of shoes. Farmer's Market Author's TableNM Book Association sponsors the table, exhibitors must be members of NMBA. For further information about exhibiting, please contact Maxine Davenport: [email protected]. Authors present on October 10, from left to right (and latest publication):

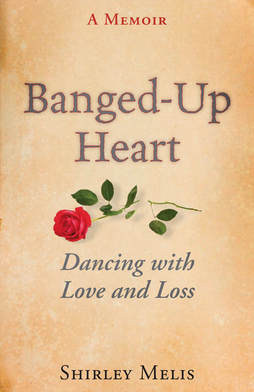

Maxine Neely Davenport ("Love is a Legal Affair") Shirley Melis ("Banged-Up Heart") Roberta Parry ("Killing Time") Tom Lohr ("Command Decision") Belinda Perry (pen name: William Luckey, "Time Alone")  “It’s too grim.” College classmate and author Leslie Garis stared at the poster displaying the cover of my not-yet-completed memoir, Banged-Up Heart. “What do you think?” she asked Marjorie, standing nearby. “I agree. Can you re-take the photo?” I swallowed hard and shook my head no. To gauge classmates’ interest in my memoir, I’d asked a graphic artist to create a poster display for my college reunion. I gave her a photo of a burned out forest -- skeletal black trees, some standing and others strewn like matchsticks across a carpet of green grasses – to use as a book cover. To me the grasses symbolized re-growth. Perfect for my memoir, which is about courage and resilience in the face of heartbreak. And especially meaningful because my story focuses on my life with John who took the photo. But in the poster, the grasses looked more beige than green, almost invisible. My classmates were right: too grim. Even if the grasses were greener, the overwhelming feeling was one of desolation. Reluctantly, I gave up the idea of John’s forest photo as a cover. Months later, after landing a publisher, I found myself facing the cover question with a deadline looming. “Take a look at memoirs in bookstores and see what kinds of covers grab you,” my publicist suggested. In the bookstore I found several with forest covers but these books were about actual treks through forests. The covers that grabbed me were brighter in color but I was no closer to knowing what I wanted. Audibly fretting, I heeded the advice of artist friend Lewis Hawkins: “Get a pencil and paper and start doodling. You’ll come up with something.” At breakfast one morning, I showed my doodle -- banged-up looking letters for the title separated from the subtitle by a rose – to my husband Frank. “Here,” he said, pencil in hand. “Break the stem of the rose.” Eureka! By breaking the rose stem, he captured the essence of my subtitle, Dancing with Love and Loss. I shared our doodle with friends at dinner who applauded. Why the rose? I can’t tell you. It must have been subconscious. In fact, roses frequently appear in my memoir. But it was graphic artist Scott Gerber, publisher of Terra Nova Books, who turned my doodle into a winner. The cover of Banged-Up Heart: Dancing with Love and Loss won first place in the 2017 Southwest Book Design and Production Awards competition.  My brother Al, my only sibling, died on March 22, 2017. His death, ending a life whose quality declined dramatically a few weeks earlier, was not unexpected. Today, after speaking at his memorial service where I felt remarkably composed, I’m convulsed by an inexplicable grief sweeping through my body. Our relationship was complicated but it was like no other in either of our lives. Al was the only person who knew my parents and others in our small family as I did. We were close enough in age to know each other’s friends. And Colusa, California, where we grew up, was small enough that we knew our parents’ friends, too. In February I spent parts of three days with Al at The Cottages at Clear Lake in Houston, Texas. Together we reminisced about our lives growing up in Colusa at 549 Parkhill Street, in a white clapboard cottage-style house fronted by a large elm tree. In the backyard, behind a cedar fence, a garden of roses -- Peace and other varieties -- opened onto a lawn large enough for a good game of croquet and a patio with a Ping-Pong table and a grill. We spent many evenings as a family in the backyard, the two of us often trying to best our father who was a champion croquet and Ping-Pong player. Al was a bright little boy. He amazed me, my parents and grandparents plus an uncle of two when, at the age of six, he recited from memory that well known poem, “A Visit from St.Nicholas” or “Twas the Night Before Christmas” – all 56 lines. Al harbored a special feeling about Christmas – the magic of Christmas – especially when he was an adult with young children. I remember being with his family in Virginia Beach one Christmas Eve. After the children were sent to bed, the adults feverishly assembled a dollhouse and train set and wrapped last-minute stocking stuffers. Happily exhausted, we dropped into bed only to be awakened at 3 a.m. by the sound of sleigh bells. Al was on the roof jingling bells, signaling that Santa was in the ‘hood. And the next morning, proof of Santa’s visit was on display for all to see. Summer vacations often found us driving north to Oregon to visit our grandparents. Both sets lived on farms. Orchards of cherry trees and a few filbert trees covered the hills of my mother’s parents’ farm outside Salem, Oregon. Eager to make a few pennies of our own, Al and I would join the hired hands, carefully picking Bing and other kinds of cherries – with the stems on -- filling one or more boxes over the course of a morning. We usually visited my father’s parents in Mist, Oregon – on the Nehalem River -- during hay-baling season. Al and I were too young to bale hay but not too young to wander down to the creek that ran behind the cow pasture where we’d catch crayfish. After delivering a catch to our grandmother, we’d walk about a mile to the General Store to stock up on black licorice. Until the General Store burned to the ground about ten years ago, it was the oldest continuously running business in the state of Oregon. Memories of those days with my brother -- catching crayfish, collecting eggs from under the hens in the henhouse, picking wild blackberries, hovering nearby while our father milked a cow, squirting sudsy warm milk into our hand-held cups, and playing hide-and-seek among the bales of hay in the barn – feel still-fresh. It was a simpler time, no electronic distractions. Before moving to 549 Parkhill Street in Colusa, we lived outside Colusa on a ranch, in a large house my parents rented. One day Al and I were riding new bicycles, exploring dirt and gravel roadways when we spotted a cluster of buildings. One looked abandoned, with a lot of dirt-stained windows. I don’t know what possessed us to toss rocks at those windows but we didn’t stop until we’d broken all twenty! We didn’t say a word to anyone. But a couple of weeks later, the owner of the ranch paid a visit to our parents – how he knew Al and I were the culprits, I’ll never know. We received a strong verbal reprimand from our father and a lesson we both learned: Don’t mess with other people’s property, even an abandoned chicken house! Like my father, Al was a big tease, and I was an easy target. Sometimes I’d get so upset, I’d run to my parents to complain. “Shirley, just consider the source,” was their usual response. With my parents’ lack of empathy and Al’s continuing teasing, I made a deliberate effort to develop a thicker skin. And then one day sweet revenge flew into my life: Well after midnight, an owl trapped in the attic of the old ranch house found an opening into my brother’s bedroom. Sounds of the owl flying into walls mingled with the terrified screams of my brother, woke the rest of us. From that moment on, whenever the spirit moved me, I would simply mimic the sounds of a hooting owl and enjoy seeing my brother visibly wince. Al loved all the pets he ever had, and he collected a lot of them – from gerbils and hamsters to lizards, including a special chameleon. One Saturday while Al was away, I heard a shriek from his bedroom. Running in, I found the house cleaner Rosetta trembling, her eyes riveted on a green curtain above Al’s bed. Staring back at us was a freshly dusted green chameleon. When Al heard the story, his concern was not for Rosetta but for the health of his chameleon. My brother had a palette for good-tasting food, not gourmet or healthful but good-tasting. He flew from Houston to northern Virginia to help my husband and me move from one house into another. The morning after the big move, I had nothing to serve anyone for breakfast. Al suggested we go to McDonald’s. On this visit to McDonald’s, my first fast-food experience, Al introduced me to an Egg McMuffin. Delicious! On a trip to Houston, Al took me out for breakfast where he introduced me to biscuits and gravy, “a Texas specialty,” he said.  At the U.S. Coast Guard Academy, Al was deemed a “marksman” for which he received a gun, a revolver. Ironically, he may have been a marksman but he was no hunter. Although a carnivore, he told me he felt guilty about eating meat. “So, eat fish!” I said. “I even feel guilty about eating shrimp,” he replied. Like me, he expressed a vegetarian sentiment but never made the leap. While a cadet at the Coast Guard academy, Al visited me at Vassar where he got into a heated discussion with one of my bright roommates about the ramifications of some historical event. He said he loved it because he didn’t often have many opportunities for such discussions at the academy. I’d hoped he would go to a liberal arts college and study law but that was my dream, not his. And then there were the girls. My college roommate Ann remembers Al as “drop-dead gorgeous.” She told me her sister had a crush on him for years. I heard this about him from other females but to me he was simply my brother. In later years we didn’t see much of each other, but we did have some long phone conversations. His memory for family incidents was far keener than mine. “Don’t you remember that, Shir?” he’d say. And when I didn’t, he’d happily fill in the gaps. During these conversations he delighted in sharing some bit of new information he’d gleaned from watching the Discovery channel or relating the plot of a movie recently seen. One of his favorite actors was Matt Damon. I think he’d seen all of his movies. Al surprised me sometimes. Two years after the death of my first husband, I called Al to tell him I was re-marrying, someone he’d never met. “Do you want me to give you away?” he asked. I laughed. At my age I figured I didn’t need to be given away. But Al and his wife Nancy flew from Houston to Virginia for the wedding where he did, in fact, give me away. Five years ago, I sent Al the first draft of my memoir – he was in it and I wanted his reaction. Two weeks later, he called: “Shir, your memoir is going to be a success. Nancy agrees.” “I hope you’re right,” I said, “but I have a lot of rewriting to do, and once that’s done, I have to find an agent and a publisher.” My memoir was published five weeks before Al died. And while he will live on in my memoir and in my heart, I grieve because I've lost a visible and irreplaceable bridge to our shared past. When owner Dorothy Massey offered me a Reading/Signing at Collected Works, I was euphoric. Reading at Collected Works, Santa Fe’s #1 independent bookstore, would be a dream come true. But what parts of my 300-page memoir would I read?

“You need a program,” said editor Morgan Farley, who suggested I take a look at some author videos on YouTube. I clicked on a YouTube of one author who impressed me because she looked and sounded spontaneous. Much to my surprise, I found when clicking onto her other YouTube videos that she’d repeated the same “program” time after time. Heartened by the idea that I might put together a reading I could use more than once, I selected passages that followed my story line without revealing the ending. For a practice reading in front of Morgan, I copied pages from a pdf of my book. Squinting to read without my glasses and rushing through the passages, I could see the disappointment in Morgan’s face. “You have time,” she said, “to make this good. I’ve heard you read before; I know you can do it. You can find a recording machine at Best Buy for $100. Get one and listen to yourself.” Over the next few days, I made a few decisions:

For the next few mornings, I practiced my patter aloud during 30-minute treadmill sessions. I wanted to memorize it so that I could look up and out at the audience except when looking down to read the passages. In the afternoons, when nobody was around, I’d tape myself. Eventually, I was satisfied with my reading, my voice inflections and pauses. (Morgan, a poet who reads beautifully, was a great help with this.) And then there was the question of using a microphone. At Collected Works, I would be on a small stage, a platform three giant steps above the main floor. One afternoon, about a week before my reading, Dorothy arranged for one of her staff to set up the microphone so I could test the sound and determine how close I needed to be to the mouthpiece. She offered a music stand onto which I’d drop my pages as I read. The day of my reading, I awoke feeling a little nervous but as ready as I could be. That evening, before an audience of 115, I learned that my initial concerns, subsequent decisions and practice paid off.  Uncomfortable in small spaces or at great heights, e.g., in a small elevator or on a ferris wheel that stops when I’m at the top, I try to avoid them and when I can’t, I grit my teeth or close my eyes and tell myself I’m going to be okay. So far so good. I have a goddaughter who turned fear on its head. Afraid of flying, of insects and closed-in spaces, she confronted her phobias, channeling them into a successful book series, School of Fear, for middle school students. Acknowledging her crippling fears and developing ways to cope, she’s now a frequent flyer able to live a full life without phobia paralysis. “I still don’t enjoy flying,” she says, “but I’ve figured out what to do to help me stay on a plane.” Good thing, too. Living in Madrid, she’s often on planes to the U.S., to see her publisher, family and friends.  How often does fear, real or imagined, influence the choices you make? Prevent you from doing things you later regret? A distressing emotion, fear can sometimes override common sense. Other times it might save your life. Knowing the difference is key. Watching the televised opening of the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro last summer brought it home – Brazil’s spectacular natural and man-made wonders, diverse ethnicities, Brazilians’ exuberance, passion for partying despite economic and political challenges – and to think we nearly missed experiencing these because of the fear factor. Last February, bombarded by a flurry of headlines in local and national newspapers screaming Zika in Brazil and warnings by friends of likely crimnal encounters, my husband Frank and I flew to Rio de Janeiro for Carnival. Zika, a virus carried by an infected Aedes mosquito, is linked to microcephaly in newborns whose mothers, when pregnant, are bitten by the infected mosquito. In my seventies, I wasn’t about to get pregnant nor was Frank a likely Zika victim. Nonetheless, we packed a couple tubes of DEET insect repellent and left showy jewelry at home. “We don’t wear repellent,” our guide volunteered our first day in Rio de Janeiro. “Rio isn’t where Zika mosquitos are.” Great news, we thought, knowing Rio would be the site for golf and other sporting events in the 2016 Summer Olympics. Who knew that four world-famous male golfers, citing Zika fear, would opt against going to Brazil to compete in an event not played in the Olympics since 1904? Do they regret their decision? Mingling shoulder-to-shoulder with Brazilians on crowded subways from dazzling Copacabana Beach to the Hippi Market in Ipanema and on mountain-scaling funiculars to view Christ the Redeemer up close and Rio from on high, no one picked our pockets. Even in the Sambadrome arena with some 90,000 spectators witnessing samba competitions by schools of 3 – 4,000 costumed singers and dancers, some on floats two- and three-stories high, we had no unsavory experiences. Caught up in the jubilation of the crowd, we cheered – dancing in place – as each school paraded the length of the arena, about a half-mile, vying for the $5 milliion first prize. We lasted until 3 a.m., seeing three of six finalists. The entire competition runs from 9:30 p.m. to 6 a.m. on successive nights. Taken by our guide to Rocinah, a “safe” favela, we admired the clean streets and colorful slum houses dotting hillsides overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. Driving back down to the center of Rio, we stopped at a Brazilian steakhouse for succulent cuts of meat barbecued, in old gaucho tradition, on an open fire – an over-the-top experience for ambivalent carnivores. From Rio we flew southwest to Iguacu Falls to see the magnificent spectacle of 275 waterfalls creating thunderous, wondrous curtains of white that stretch nearly two miles wide and 200 or more feet high. Their source, the Iguacu River, forms the boundary between Brazil and Argentina. Wooden stairways brought us within arms-length of the rumbling falls, allowing us to sense the power of falling water, not a few gallons but millions of barrels. Still, no mosquitos. Up north in Manaus, awaiting a riverboat that would take us onto the Amazon and into the rain forest, we walked through the Adolpho Lisboa Municpal Market, a cast-iron replica in miniature of Paris’s Les Halles market building. Later, we ventured into the city’s famed opera house, the opulent Teatro Amazonas, where the Amazonas Philharmonic Orchestra was rehearsing Beethoven’s Ninth. Comfortably seated inside this Renaissance jewel built in the late 1800s, I let the music fill my body while my eyes feasted on tiers of gold-leafed columns, chandeliers (198 imported from Italy including some of Murano glass) and the ornate ceiling of painted panels depicting music, dance and drama. Only after leaving the opera house did I focus on its exterior – walls painted a dusty rose, accented by white columns, and a dome covered with thousands of ceramic tiles painted the colors of Brazil’s national flag – green, yellow, blue and a little white. We had expected Manaus to be a village dominated by the opera house built when fortunes were made in rubber. Instead, we found a city teeming with some two million inhabitants and an ever-growing presence of high-tech companies.  Our cruise on the Amazon and trek through the rain forest led by an indigenous tribesman who showed us how to survive in the forest left me with one regret. I’d hoped to see hundreds of wild birds, including toucans noted for their large colorful bills, but the birds were few and the only toucan I saw was in the Manaus zoo. After two weeks in Brazil, I’m hard-pressed to describe the looks of a Brazilian. Descendants of early settlers and post-colonial immigrants – Portuguese, Italian, Spaniards and Germans with large numbers of Japanese, Poles and Lebanese – African slaves and Brazil’s indigenous peoples, they, like those of us in the United States, are not a homogeneous lot. We were told that the largest Japanese community outside Japan – some 2 million -- lives in Sao Paulo. Our last day in Manaus a mosquito flitted by while I was eyeing souvenirs in a shop in our hotel complex. Wearing repellent, I was relatively fearless. According to one authority, our chances of being killed by a car in the U.S. are 17,400 times greater than contracting Zika from a mosquito in Brazil. If we’d given way to unexamined fear, we might never have experienced the richness of Brazil and Brazilians’ unabashed passions. Pressed to come up with a subtitle for Banged-Up Heart -- in time for a poster display at my college reunion -- I quickly settled on A Widow’s Story of Star-Crossed Love. It wasn’t until many months later, about the time I landed a publisher, that I began to lament my hastily concocted subtitle. A potential reader might think my book was about a widow who falls in love with someone who dumps her, and that was not the case. Why hadn’t I seen that earlier? If a subtitle tells the reader what the memoir is about, what was my memoir really about? “Love and loss,” I said to my editor, who’d asked the question. She nodded her agreement. But the words “love and loss” alone seemed incomplete. What was it about love and loss that would give the reader insight into the essence of Banged-Up Heart?

My thoughts turned to the Anne Lamott Plan B piece where I’d found my title, and that’s when it hit me. The subtitle should say something about dancing. I ran a couple of possibilities by Terra Nova Books editor, Marty Gerber: “How about A Widow Dances with Love and Loss?” “Yes,” he said, “you were widowed at the start; yes, you’re twice widowed at the end. But in between is the story of two diverse individuals – powered by love—trying valiantly to know each other and find a way together to battle an overwhelming enemy. I simply feel that the ‘human-ness’ of the tale you tell is so much more than the ‘widow-ness’ angle.” “How about A Dance with Love and Loss?” I asked. “It’s not a single dance,” he said. “You’re dancing with love and loss from beginning to end.” And that’s how the subtitle, Dancing with Love and Loss, came to be. Sometimes it takes time and distance to be able to re-focus effectively on the essence of what you’ve written. And having the reaction of someone else, such as editor Marty Gerber, can prove invaluable.  “Send your creative works for display at Reunion.” My college reunion was three months off but, regrettably, my memoir, my creative work, was not finished. I was still rewriting with no likelihood of completing it in time. But what an opportunity to promote it! I thought. I might even find the name of a literary agent from an author classmate. My editor agreed. With her encouragement, I met with Amiel Gervers, a tall brunette who’d left an advertising career in New York City to live in Santa Fe, New Mexico. “Shirley, I can design a website for your book, and I can have it finished with posters and postcards in time for your college reunion.” Stirring sugar into her tea at the Teahouse on Canyon Road, Amiel told me what she’d need. “First, I want to read your book. I know you haven’t finished rewriting it, but that’s all right. I want to select quotes to go with some of these photos you’ve shown me. You’ll need to send these to me electronically. Also, I’ll need a bio from you and while you at it, something about your “Tahoe Traveler” writing experience. In my twenties, I’d traveled in Europe and the Middle East, writing a column for the Tahoe Daily Tribune. Within days, Amiel had everything she needed from me with one exception: a title for the book. I’d sent her a photo to use as a cover mock-up -- a burned out forest with nascent green grass denoting regrowth in the foreground. But I was still clueless about a title. Months earlier, I’d discarded a working title, Love + Loss x Two, because I’d narrowed my focus to my recent love and loss. Hoping for an epiphany, I hunkered down with the last several chapters. I would be discussing one, possibly more, of these with my editor in a few days. In one chapter, my attention riveted on a selection by writer Anne Lamott that the Rev. Kim Beach read at John’s memorial service. That’s it! I thought. Eager to share my find with editor Morgan Farley, I could hardly contain myself as I sat down at the table for our editing session. “I have a title!” I blurted. “So do I,” she said. “Banged-Up Heart,” I said. “That’s what I came up with, too.” Morgan beamed with delight. And that’s the story of how I found a title for my memoir – in time to promote it at my college Reunion. Since then, the cover has changed but the title remains.  A few months after my husband’s death, I told close friends I was going to write about my life with him, cut short two years after we married. I felt blindsided, but by what I didn’t know. By John? By my own naivete? I had to figure it out. A writer most of my life, I was comfortable putting pen to paper. Aided by a journal I’d kept and a boatload of emails I’d written during John’s last months, I set out to tell my bittersweet story. After two years of grieving for my first husband, I’d been swept up into a whirlwind romance by a younger man who was a rocket scientist. We married and created an adventurous new life together. We were supremely happy – and then I lost him to a brain tumor. Day and night, in Santa Fe and Reston, Va., I sat at the computer, my fingers flying across the keyboard, capturing the essence of my two-year odyssey. Friends read my drafts and came back with questions that caused me to re-think and re-write. Over tea at Collected Works Bookstore in Santa Fe, I handed my manuscript to editor Morgan Farley. “I’ve been writing for three years, and this is what I’ve produced,” I said. “I know there’s something missing but I don’t know what it is.” “I know what’s missing,” Morgan said in a phone call a couple of weeks later. Relief washing through my body, I grabbed a pen to schedule another meeting. “You have three books in one,” she began. “I’ve made a note of the pages devoted to each and would suggest you go with the one that has the most pages because that seems to be where your strongest energy is.” I’d started off on the energized track, but a close friend who’d known and loved my first husband Joe suggested I also write about my life with him. Once I’d done that I thought, Why not write about my life before Joe – about Nikos in Greece and while I’m at it, my troubled mother? Back on track, I listened to Morgan talk about the craft of novel writing and how it applies to writing memoir. She explained that a story comes alive when you create scenes to show action, and use dialogue to reveal personality and character. We talked about using description but not too much, to allow the reader to use her imagination, and pacing by relieving highly charged scenes with narrative while keeping the story moving. It was a lot for me to absorb. A history major in college, I hadn’t read many novels; I’d read original sources and become practiced at critiquing authors’ premises and their use of sources to back them. Later, in my professional life, I did a lot of business writing – press releases where scene-setting meant naming the place where a meeting was held and dialogue meant adding direct quotations by speakers that revealed neither personality nor character. Rewriting my memoir to give it the missing ingredients sounded challenging. “If you choose to do this, it will be transformative,” Morgan said. Over the ensuing months, Morgan frequently asked, “What were you feeling?” – inviting me to dig deep for my interior emotional state. She helped me to confront my story as I lived it, subjectively, and to reflect, time and again, on the significance of my feelings, thoughts and actions. Looking deep inside to find my truths, when I wasn’t by inclination introspective, challenged me. Having the courage to put them on paper, even those I might not like, meant overcoming my own inhibitions and ignoring the advice of well-meaning friends who believed personal publicity of any sort should be limited to births, marriages and deaths. “It’s too personal,” a good friend confided after reading the first several pages. The greatest joy in writing Banged-Up Heart was hearing Morgan say, “Beautiful, beautifully expressed.” Or, “I just kept reading, forgetting I was supposed to be editing.” I also heard from Morgan, “Shirley, I’m sorry but this doesn’t work.” And I’d toss eight hours worth of carefully crafted prose. The successive joys of landing a top-notch agent, Liz Trupin-Pulli, and a publisher, Terra Nova Books, are more than icing on the cake. They’ve made it possible for me to bring my years of hard work to fruition. |

Author BLOG

I'm Shirley Melis. You may know me as Shirley M. Nagelschmidt, Shirley M. Bessey and now, Shirley M. Hirsch. Each reflects a particular phase of my life. Banged-Up Heart is a slice of my life's journey and in telling my story, I'm giving voice to my long silent "M" by reclaiming my maiden name, Shirley Melis. Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed